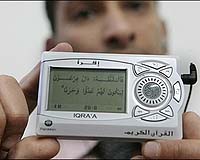

An Egyptain salesman holds up a digital Koran in Cairo. Cairo residents, already summoned to prayers five times a day by a chorus of scratchy loudspeakers, are now clamouring for a new line of portable electronic devices to show their devotion to Islam. Photo courtesy AFP. |

Cairo (AFP) April 18, 2007

Cairo residents, already summoned to prayers five times a day by a chorus of scratchy loudspeakers, are now clamouring for a new line of portable electronic devices to show their devotion to Islam.

Digital Korans, automatic prayer reciters and headphones dispensing religious advice are all part of the growing wave of outward religiosity that is increasingly defining daily life in Egypt.

"As a Muslim, I find that hearing these prayers bodes well for the rest of the day,"said Osama Abdel Hamid, an economics professor at Cairo University, as he searched through a busy car parts market for an electronic prayer-reciter.

The little black speaker box that appeared a few months ago is catching on quickly among Cairo's cab drivers, who wire it up so that the prayers pour out the moment they open the door or turn the ignition.

It's slightly more pious than the "It's a Small World After All" jingle that are heard from taxis when they hit the brakes, melding with the constant din of horns and shouting in the city of 16 million people.

Mohammed Mahmud, a seller of car parts and gadgets in the city's Tawfiqiyah market, says the Chinese-made devices have become very popular in recent months.

"You can also put them in elevators," added Mahmud, from his stall in one of the city's oldest markets, where fruit and vegetable sellers are slowly giving way to the peddlers of the trinkets, noise-makers, and assorted kitsch that adorn Cairo taxis.

The little black speakers sell for only seven Egyptian pounds (a little over a dollar), but Abdel Hamid, the economics professor, admitted he was actually looking for a better quality Thai-made model since the Chinese one he bought "fried after about an hour."

The devout can find a more upscale model in the "Ayat," which was recently exhibited at the GITEX exposition in Dubai, the largest information technology and communication fair in the region.

Resembling a fancy pair of earphones, the Ayat can give the wearer advice, in Arabic or English, on the number of prostrations necessary for each type of prayer. It also plays Koranic verses.

"The idea came to me on a plane when I was listening to my iPod," said developer Sherif Danesh, an Egyptian living in California's Silicon Valley.

"Many people of all religions are hungry for information on their religion these days," he told AFP by e-mail. "The availability of small portable inexpensive audio and video devices is making it very easy to access such information anywhere, anytime."

Putting Koranic verses and prayers into electronic format can be a fraught enterprise, however, as a number of manufacturers discovered in 2005 when Egypt's Grand Mufti Ali Gomaa condemned the use of verses as ring tones.

Gomaa, one of the highest authorities for Sunni Islam in Egypt, described it as "a devaluing of the sacred book."

Danesh said he was careful to get the necessary approval before developing Ayat, and said he had already sold several thousand of the devices, which cost 380 pounds (67 dollars, 49 euros).

The proliferation of Islamic gadgets cuts across markets, ranging in complexity from an alarm clock for the five daily prayers with a built-in compass pointing towards Mecca, to an entirely digital Koran accompanied by the hadith (traditions) of the Prophet Mohammed.

At 1,200 pounds (210 dollars), however, the electronic Koran is pretty far outside the average Egyptian's reach.

Many see the gadgets as part of the public piety that increasingly pervades Egyptian society, where the vast majority of women wear religious headscarves and an increasing number of men sport the "zebiba" -- a prune-like bruise on the forehead that supposedly comes from vigorous praying.

Dalal al-Bizri, a columnist for the pan-Arab daily Al-Hayat, sees the devices as evidence of the importance of appearances in contemporary Islam.

"It's a religion whose followers seem to need to touch, to feel the beyond -- much like the pagans they once condemned," she said, adding that such outward displays betray "an insistence on belief, as though some deeper conviction was lacking."

Sociologist Saad Eddin Ibrahim, on the other hand, thinks the trend is more indicative of the "naivety of the consumers and the intelligence of the merchants."

"It also says a lot about how quickly the Chinese economy reacts and adapts to the desires of the consumers -- whoever they are," he said with a smile.

No comments:

Post a Comment